Close your eyes and picture this:

Today is THE big day – you have practiced years, months, and days. You have poured your hours, minutes, and seconds into training and gymming. You had to restrict your diet and control yourself in the presence of the infamous bubble tea and fried food. You had sacrificed your social time to rest and recuperate in preparation for the tougher, more vigorous training for the next day. All this preparation done but the truth is – you can’t help but feel the jitters! You’re sitting at the locker room or waiting for your turn at the call room, and your heart’s pumping faster than a sprint or you’re feeling the pins and needles all over your body. This phenomenon is commonly known as performance anxiety.

Performance anxiety is defined as an intense fear of negative outcomes that arises before and during significant tasks (Olivine, 2024). According to Ford et al. (2017), performance anxiety positions individuals into a state of apprehension. It is driven by the stress associated with task outcomes and expectations under pressure, frequently occurring among employees, students, and especially athletes (Biswal & Srivastava, 2022). This anxiety manifests in two ways – either as trait anxiety, a more stable personality characteristic, or as state anxiety, which is more temporary and situation-specific (Weinberg & Gould, 2015). Rowland and Lankveld (2019) estimates that 30 to 60 percent of athletes have experienced sports-related performance anxiety (SPA).

Symptoms of SPA can be categorized into somatic, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral responses (Forsyth & Eifert, 2016; Laguaite, 2021; Ford et al., 2017; Marks, 2021; Olivine, 2024; Marks, 2024; Weinberg & Gould, 2015). Varying in intensity from mild to severe, SPA symptoms differ among individuals and can also vary within the same person across different episodes (Olivine, 2024). Whether experienced individually or in combination, these symptoms can cause considerable distress, leading to a spiral of negative affect that diminishes self-confidence and impairs focus.

Somatic symptoms

- Increased heart rate and blood pressure

- Fast and shallow breathing

- Sweating – cold hands/feet

- Muscle tension

- Dizziness and light-headedness

- Tremors

Emotional symptoms

- Fear

- Worry

- Self-doubt

- Embarrassment

- Helplessness

- Apprehension

Cognitive symptoms

- Excessive self-criticism

- Unrealistic expectations

- Heightened focus on failure

- Inattention

Behavioral symptoms

- Withdraw from social interactions

- Display impaired performances

- Decide not to compete/train

- Self-sabotage

- Fidgeting (biting fingernails etc)

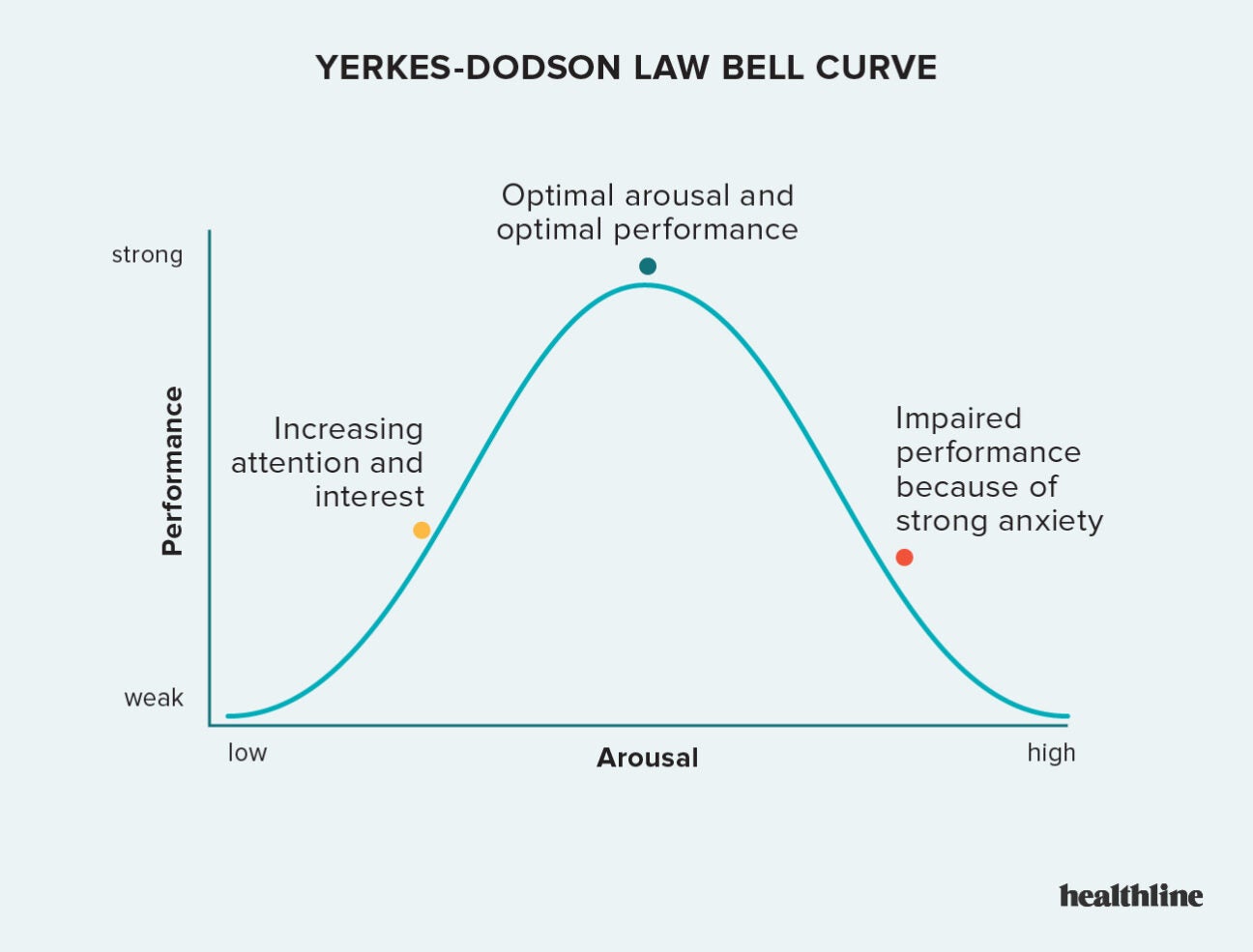

Previous research has explored the origins of SPA – one theoretical example would be the Yerkes-Dodson law (Yerkes & Dodson, 1908). A model depicting the relationship between stress and task performance, it suggests that optimal performance is achieved at an intermediate level of arousal, synonymously referred to as stress. Both insufficient and excessive arousal can lead to diminished performance. This concept is known as the inverted-U model of arousal (Swaim, 2022).

The horizontal axis indicates the level of arousal and the vertical axis represents the degree of performance. The ideal state of arousal and performance occurs at the midpoint of the curve.

The Yerkes-Dodson law (Pietrangelo, 2020) asserts that as arousal increases, the ability to perform tasks improves, providing sufficient motivation. This effect lasts up to a certain point – referred to as the optimal level. Beyond this point, performance begins to decline, as excessive arousal and anxiety hinders the ability to excel.

What does an optimal level of arousal feel like?

Your heart beats faster than usual; your body and brain are all fired up; you feel a sense of alertness and clarity. It’s the adrenaline rush that you get when you huddle before your match or get up the blocks when the whistle blows. You know that you’ve got what it takes – the stress is manageable, motivational, and performance enhancing.

What does a high level of arousal feel like?

It’s the final play of the season, the finals of the event – the winner takes all. Your heart beats faster than usual, but it is unsettling, nerve-wrecking, and distracting. You know you’re prepared but the thought of losing kept creeping in. You try to get your head back in the game, but you’ve lost focus – the stress is too much that it is working against you.

Whilst all athletes aim to achieve the optimal level of arousal, it is crucial that it differs from person to person, depending on the specific tasks, degree of skill, and confidence level. Reaching the optimal arousal zone can be challenging, as some influence factors are beyond anyone’s control. Nonetheless, SPA is a natural response, especially when the stakes are high. Beyond being ready physically, it is also important to take care of yourself mentally. Focus on identifying and replacing irrational thoughts with kinder, more compassionate ones.

Remember that nobody is perfect, and nobody expects you to be. It’s perfectly okay to make mistakes – it’s a part of finding yourself.

Written by:

Jamie Ang Hui Hsien

Singapore Institute of Management – University at Buffalo, State University of New York

References:

Biswal, K., & Srivastava, B. L. (2022). Mindfulness-based practices, psychological capital, burnout and performance anxiety. Development and Learning in Organizations, 36(6), 4 – 7.

Ford, J. L., Ildefonso, K., Jones, M. L., & Arvinen-Barrow, M. (2017). Sport-related anxiety: Current insights. Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine, 8, 205 – 212. DOI: 10.2147/OAJSM.S125845

Forsyth, J. P., & Eifert, G. H. (2016). The mindfulness & acceptance workbook for anxiety: A guide to breaking free from anxiety, phobias & worry using acceptance & commitment therapy. New Harbinger.

Laguaite, M. (2021, April 5). Workplace anxiety: Causes, symptoms, and treatment. WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/anxiety-panic/guide/stage-fright-performance-anxiety

Marks, H. (2021, November 13). Overcoming performance anxiety in music, acting, sports, and more. WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/anxiety-panic/guide/stage-fright-performance-anxiety.

Marks, H. (2024, February 27). Stage fright (performance anxiety). WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/anxiety-panic/stage-fright-performance-anxiety

Olivine, A. (2024, April 1). What is performance anxiety? Very Well Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com/performance-anxiety-5200716#:~:text=Performance%20anxiety%20is%20an%20excessive,where%20they%20have%20to%20perform

Pietrangelo, A. (2020, October, 2020). What the Yerkes-Dodson Law says about stress and performance. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/yerkes-dodson-law

Rowland, D. L., & van Lankveld, J. J. D. M. (2019). Anxiety and performance in sex, sport, and stage: Identifying common ground. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(1615), 1 – 21. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01615

Swaim, E. (2022, March 9). What causes sports anxiety? Plus, tips to get your game (back) on. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/sports-performance-anxiety

Weinberg, R. S., & Gould, D. (2015). Foundations of Sport and Exercise Psychology (6th ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Yerkes, R. M., & Dodson, J. D. (1908). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit formation. The Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology, 18(5), 459 – 482. DOI: 10.1002/cne.920180503

Leave A Comment